Michael Karam

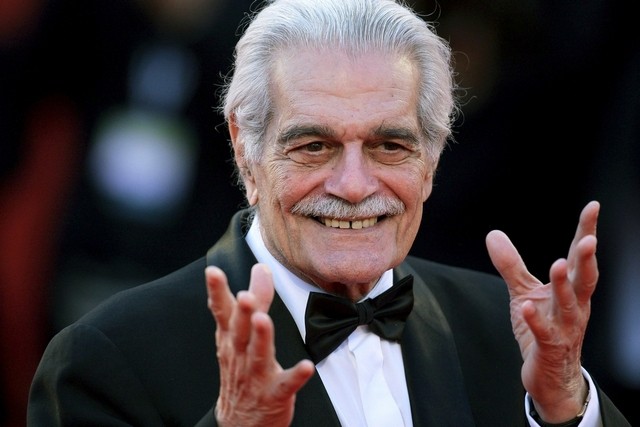

When the Egyptian actor Omar Sharif died on Friday, many Lebanese were quick to claim him as their own. In many ways they were right to do so, as the world’s media was big-hearted enough to recognise Sharif’s roots.

Born Michel Shalhoub, he grew up in a small Greek Catholic community from the Cairo suburb of Heliopolis, many of whose residents – my mother’s family included – came from the Bekaa Valley town of Zahleh in the 19th century. “They were our neighbours,” she said when I called, tongue firmly in cheek, to offer my condolences.

Not since the Apple founder Steve Jobs, an American of Syrian descent (close enough given we were once the same country) died in 2011, has there been such a fuss over claiming an emigrant son. But then again, the Lebanese love to list the dozens of famous compatriots who have made it abroad. And to be fair (given the mediocrity of those who run the show at home), for such a small country we do punch above our weight.

For openers we can claim Carlos Slim, the Mexican telecoms mogul often cited as the richest man in the world. But we can also point to a stellar list of actors, writers, artists, designers, doctors and businessmen – all of whom can trace their origins back to Lebanon.

At a talk at the American University of Beirut in the spring of 2010, Mr Slim reminded those gathered of the ability of the Lebanese to set off with nothing and make a go of it in whatever country they landed in. The earliest Australian tinkers – hawkers of cheap goods – were Lebanese and Syrians who probably had no idea where they had ended up after boarding the boat at Beirut, but laid the foundations for what is now a thriving, prosperous and hard-working expatriate community. They did the same in West and Central Africa, Canada, Brazil and the United States, where the Michigan town of Dearborn could be twinned with anywhere in south Lebanon, such is the influence of the predominantly Shia Lebanese population

All this is nothing new, but I mention it because the sad – yes, sad – tradition of emigration is still very much alive, such is the level of desperation back home.

At Sunday lunch last week in my village I met a man who had been made redundant from a decent job in the hospitality sector in Oman. He had returned to Lebanon with his young family but was not planning on sticking around, such was the dearth of opportunities in a country that is focusing all its efforts on not imploding. I asked him where he wanted to go. “I don’t care,” he shrugged. “Anywhere. The trouble is not many countries are giving visas to the Lebanese nowadays.”

In the 24 years since I returned to Lebanon – a period when the country was dusting itself down after 15 years of civil war – I have not felt such a palpable sense gloom as I did last week. And yet the country and its people have so much to offer if they are only given a chance.

Certain elements of the political class (Michel Aoun, I’m looking at you) are so hell-bent in achieving their own narrow sectarian interests that if they are not careful there will no be a country left in which to implement their outrageously self-seeking agendas.

I lived through two wars, a popular revolution, an attempted coup, a bombing campaign and too many political crises to mention, but even then Lebanon was always able to bounce back.

I still recall in wonder how everyone went back to work the day after the ceasefire in the 31-day war between Israel and Hizbollah in the summer of 2006. One million people had been displaced and material damage ran into the billions of US dollars, but we just rolled up our sleeves and cracked on – and within months the tourists were back.

If there is a glimmer of hope, it is that the Lebanese have been here before and will continue to tread that perilous path between emigration and digging in for the long haul. In the meantime, as was the case for a certain Michel Shalhoub whose family left Zahleh for Cairo, when we leave, every now and then we can take on the world and win.

Michael Karam is a freelance writer who lives between Beirut and Brighton