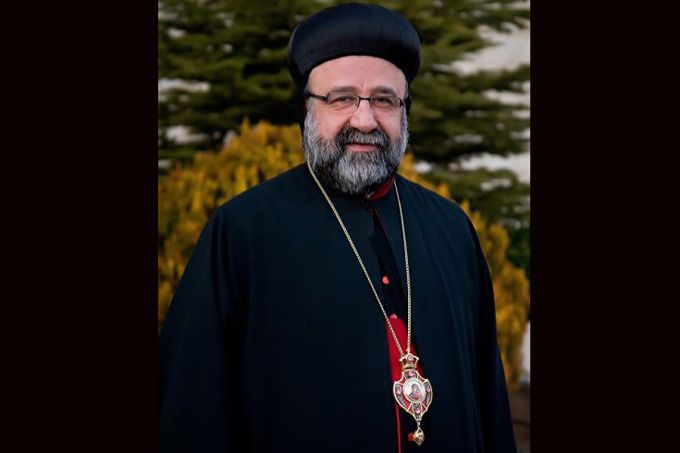

.- On April 22, 2013, both the Greek and Syriac Orthodox archbishops of Aleppo, Boulos Yazigi and Gregorios Yohanna Ibrahim, were kidnapped in Syria near the Turkish border. Their driver, Deacon Fatha' Allah Kabboud, was killed. Today, 23 months later, the bishops remain missing – though for some time it has been rumored that only one of them is still alive. The bishops were abducted on their way back from the Turkish border, where they were negotiating the release of two priests, Fathers Michael Kayyal and Maher Mahfouz, who had themselves been kidnapped in February 2013.

Archbishop Ibrahim and Archbishop Yazigi are only two of the multitude of victims of the Syrian civil war, which today is entering its fifth year. The war has claimed the lives of more than 220,000 people. There are 3.9 million Syrian refugees in nearby countries, most of them in Turkey and Lebanon, and an additional 8 million Syrian people are believed to have been internally displaced by the war.

On March 15, 2011, demonstrations sprang up in Syria protesting the rule of Bashar al-Assad, the nation's president and leader of its Ba'ath Party. The next month, the Syrian army began to deploy to put down the uprisings, firing on protesters.

Since then, the violence has morphed into a civil war which is being fought among the Syrian regime and a number of rebel groups: the rebels include moderates, such as the Free Syrian Army; Islamists such as al-Nusra Front and Islamic State; and Kurdish separatists.

Only about a week before his kidnapping, two years into the war, Archbishop Ibrahim had told BBC Arabic that Syrian Christians are in the same situation as their Muslim neighbors: “There is no persecution of Christians and there is no single plan to kill Christians. Everyone respects Christians. Bullets are random and not targeting the Christians because they are Christians.”

Archbishop Ibrahim had written a book in Arabic in 2006 called “Accepting the Other.” At that time, before the start of the war, Syrians of different religions lived together in peace.

An excerpt of this work, focused on “the dialogue of life,” was translated into English for Aid to the Church in Need and appears below thanks to that international Catholic charity, which has pledged $2.8 million in emergency aid for the Christians of Syria:

The plurality of religions and faiths does not foment an inter-religious conflict due to the fact that the common denominator of its teachings, heritages and ethics affirms the oneness of God and the multiplicity and integrity of its people.

Whenever Christians and Muslims approach the sources of divine teaching, they may feel that their common heritage is part and parcel of the universal belief of the relationship between man (the weak) and the Creator (the mighty). Christians say we have one God and Muslim say there is no God but God.

From this understanding of our common heritages derived the concept of the “Dialogue of Life” – to which we owe our peaceful coexistence and the flourishing of our communities. However, even given the rich ethno-religious diversity of our communal tapestry, it is not at all like the concept of multiculturalism that is emerging in Western society.

The “Dialogue of life” is a rather simple, spontaneous, and natural way of life – a sort of coexistence sustained by the values of solidarity, humanity, impartiality and accepting the other unconditionally. Some may argue that our “Dialogue of Life” draws on the principles outlined in the Geneva Convention. Not so, our “Dialogue” has its own unwritten codes, whose values far predate this relatively new Western concept of dialogue and coexistence.

The “Dialogue of Life” is an in-built intuition: its values have been well tried and tested throughout the centuries of our coexistence, both in situations of peace and war, with and without the presence of media and UN observers. There is no need for awareness classes, training courses or fundraising campaigns.

The “Dialogue of Life” starts with the first steps of a toddler in the neighbourhood, and carries on at nursery and schools, so that in adulthood people are well equipped with the basic skill to coexist and keep this dialogue alive and functional. Understandably, such values are not a commodity and certainly, may not have a sell-by date. However, they are not immune but in fact extremely sensitive to the fluctuations of security and law and order in our milieu. Therefore, they cannot be taken for granted, but need constant nurturing, maintenance and enhancements.

The “Dialogue of Life” reflects that we are all children of God, created in His image. We are all in the same boat, riding the same waves, facing the same reduced circumstances. We often find ourselves peddling in shark-infested, uncharted territories. Understandably, it is not necessary that all are able to reciprocate. But for us the principle of the survival of the fittest is not an option, and it cannot be spelled out who will come out on top. The “Dialogue of Life” hinges on accepting others and shuns religious or sectarian distinctions.

At this juncture of our history, when war has become a part of daily life, there never has been a greater need for this “Dialogue of Life.” It remains to be seen how waterproof our treasured “Dialogue of Life” and what the limits of effectiveness might be in such reduced and perilous circumstance—especially with so many outside factions coming into our country with the object of tempering with our way of life, upsetting our peaceful coexistence.

Let us hope and pray that the profound effects of civil war will not be so great as to prevent the recovery and survival of our “Dialogue of Life” and our civilized coexistence.